Limits form an integral part of our lives. As a competitive athlete, I have come to know about various types of limits over the course of my career — both mental and physical. In sport, and also in my life in general, I get to know my limits and feel my way as I approach them. I have come up against certain limits and learnt to respect them. Others I try to postpone or overcome. And again there are some limits that have not yet been reached and are waiting to be defined anew.

The limits that I experience in sport are usually imposed by nature or are set by me, my head and my body. However, the limits that society imposes on us from outside are different.

Inclusion and exclusion

People tend to want to divide and categorise everything, especially themselves. Into races, genders, religions, parties and countless more. For this purpose boundaries are drawn. Wherever boundaries are drawn, we inevitably find there are people who are excluded and majorities and minorities emerge. This can lead to major conflicts and prejudices. To a certain extent we need such categories and divisions in order to classify, create contexts and navigate our way through the world more easily. We need boundaries in order to live together, boundaries that apply equally to all, but which do not relate to the essence of the person and are not depreciative. The question is, where and to what extent are boundary lines drawn and how trenchantly. And last but not least, how we deal with and evaluate these demarcations.

It is understandable that people with a physical impairment are also named and categorised as such. However, such a classification does not always appear clear from the outside, and the boundary limits are not always clearly recognisable. Therefore the classification is repeatedly called into question. What is the definition of a disability, where does it begin and where does it end? And are we talking about a disability in the singular, that is to say a physical ailment (medical), or about disabilities in the plural in the sense of hindrances that act from outside (social) and restrict our ability?

When it comes to the subject of disability and inclusion, many people do not see this as about classification into categories. Not about ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Inclusion is rather a range or spectrum in which we all find ourselves at some point. Be it a temporary injury, an illness or, at the latest in old age.

When I look at the statistics that quantify the proportion of the population who are affected by a disability, illness or weakness, or who are exposed to an increased health risk, I suspect that sooner or later we will all be confronted with one or more infirmities and will have to accept the ‘disability’ of a hindrance caused by the infirmity itself or by hurdles as described above.

Not to pigeonhole ourselves

I sometimes notice that people with disabilities also pigeonhole themselves. They play the role of victim or give themselves a hero status. We should avoid either exalting or demeaning ourselves before others due to some characteristic/disability, and thus setting ourselves apart.

But in my opinion even campaigns by various international organisations with laudable intentions such as ‘#WeThe15’ can be misinterpreted and can segregate people with disabilities. That campaign aims to raise awareness of the rights and dignity of the 15% of the world population who are said to be affected by a disability. The campaign logo is a pie chart with a section which is meant to represent the 15%.

In my opinion, as described in the section above, it is too much about ‘us’ vs. ‘the others’. We are a part of the population just like other people with their own characteristics. Figuratively speaking, people with disabilities should not be represented as a separate piece of cake, they are an equal ingredient in the dough.

One difficulty that arises when looking at things in categories is that we are also measured against them. This creates a greater burden for those affected, because they are not granted individuality. Prejudices, valuations and stereotypes arise. We are all lumped together. If someone in a group makes a mistake, the whole group is condemned. This also leads to unconscious expectations as to how a person in the alleged separate group should behave and what role they should assume. This in turn creates pressure and stirs up the urge to prove the opposite. You strive not to stand out ‘negatively’ and not to meet these expectations of otherness, but to comply with the norm. I don’t have to be a psychologist to surmise that behaviour may be suppressed or characteristics hidden, as a consequence. To my knowledge, these phenomena are also referred to in technical language as internalised ableism. Over time, people with disabilities unconsciously internalise the prejudices and discrimination they experience, or even agree with them. They are ashamed of their disability, doubt themselves or hesitate to identify themselves as ‘disabled’.

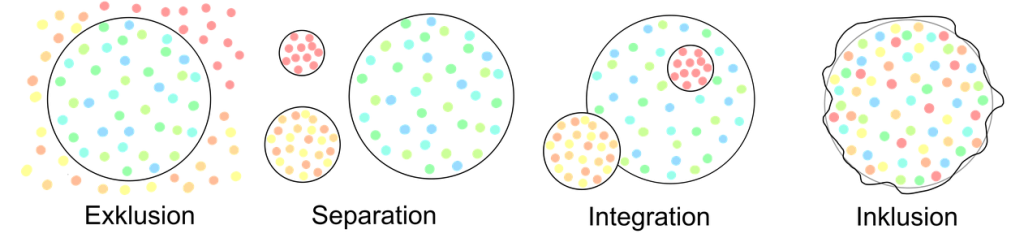

From inclusion to separation

People are excluded from a society.

Creation of separate groups/systems outside a society.

Integration of people into existing systems (e.g. schools) or societies. They are expected to adapt to the circumstances.

Unconditional equality and participation in a society. With inclusion, not only do people adapt to a prevailing system, the system also adapts to the people.

Inclusion as a vision of the future

In the past, integration was something that people were working towards, whereas today the vision of inclusion more often points the way that society should develop. It goes beyond merely the understanding of integration and encompasses all dimensions of heterogeneity. Inclusion means the unrestricted right of every individual to personal development, social participation, co-determination and co-development. The equality and common diversity of people find their place, diversity becomes the new normality. The right to inclusion is a human right and is anchored in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. All the terms mentioned above are to be understood as processes rather than states. A process for embracing human diversity. Inclusion begins in the mind of each individual.

True and lasting inclusion should happen in a natural way and not be ‘forced’, ‘staged’ or even ‘celebrated’, so that the otherness of people with an impairment is not focussed upon and highlighted even more. Good inclusion is that which emphasises commonalities, common goals, and puts the all-embracing society in the foreground. After all, we humans have more in common, more unites us than separates us from each other. This is so natural and self-evident that the day may come when society no longer needs the word ‘inclusion’. Inclusion has to happen as fast as possible, but it also needs time and patience, and has to establish itself gently but steadily in the thought patterns of society, so that it is accepted and can bring about lasting change. Still, I would say that more pressure needs to be exerted at a political level so that the long overdue changes can be embodied in law and implemented, and change can be driven forward.

We should strive to increase the visibility and participation of people with disabilities and other minorities in society. The more visible people with disabilities are, the more they fit into the overall picture. More participation in everyday life, in the working world, and indeed also in areas such as politics and the media. But this is certainly not to be based on an enforced quota, but rather on personal capacities gained through the acquisition of skills, just as it is for people without disabilities. To take one example, it is desirable for a person with a disability or other form of diversity to host a TV programme, not primarily because of their disability or diversity, but rather thanks to their acquired professional skills and abilities. After all, it does not matter whether it is a speaker with a prosthesis standing behind the lectern, or someone sitting in a chair as a wheelchair user, or a non-disabled person, as long as the content is conveyed competently in an interesting and understandable manner.